*beeeeeeeeep* "Unknown medical problem, 9876 Elsewhere Drive..." Our district.

Laughing and swearing, we piled into the ambulance. When they realized how wet I was, they laughed even hearder ... but as hot as it was, I was dry when I got there.

This was not to last.

* * * *

The call was for chest pain and near-syncope (fainting). We arrived to find an elderly woman sitting on the bed, looking a bit pale, a bit sweaty, but generally alright. We put her on some O's, start asking questions. Nearly passed out in the shower. Cardiac history. 3 out of 10 chest pain. Some shortness of breath. I was just getting the aspirin out when one of the firefighters got the monitor hooked up.

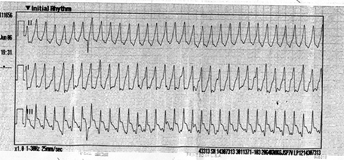

(For my non-medical readers, this is [presumed] ventricular tachycardia or v-tach, a very serious rhythm that is often seen in cardiac arrest. It's indicative of something being Very Wrong. Her heart is beating about 240 times a minute.)

((For my medical readers, while we can go back and forth all day between VT and PSVT with aberrancy, the fact is that we only have a 3-lead in the field and we treat all wide-complex tachycardias the same -- lidocaine if stable, cardiovert if unstable.))

Uh-oh. Everyone exchanges serious looks. One of the fire medics rips open the IV kit while I pull out the pads. They miss their first attempt but get their second as my preceptor and I scribble drug calculations on our gloves and agree on a dosage of lidocaine. I push the first bolus. She slows down to the 190s, but doesn't convert, and slowly begins creeping upwards again. We all conference briefly and agree to load and go, with a second bolus and lidocaine drip on the way, and cardiovert her if she becomes less stable.

I'm no longer dry.

We take off, loud and flashy. She doesn't really change enroute. The second bolus doesn't do much, and I go ahead and hang the drip anyway (my first!). Call my report. If you key up the mic with sirens in the background and wait a couple of second before talking, there's no wait for a nurse to answer.

At the hospital, she does alright for a bit. The doc looks at the 12-lead and says he's not sure if it's really VT, or SVT with a bundle branch block. He starts a beta-blocker to try and convert her.

A few moments later, while we're still standing around, she goes unresponsive and starts having gasping, agonal-type respirations. They check ... no pulse. The doc gives her a precordial thump, glances at the monitor, and barks, "Shock her!" They light her up at 300 joules and she converts right into a sinus rhythm.

She goes to the cath lab with a massive MI. No word on how she did after that.

* * * *

That was the first and best call of the day. We did a syncope, a sweet old lady with a fall, a r/o neck injury from an MVA, a kid with an allergic reaction who was stable and didn't let me touch her, and, in the middle of the night, an elderly man with new diabetes. Half an amp of D50 brought him right around, and we left him with his wife, a glass of orange juice, and a slice of pie.

"Do I chart that? Blueberry pie bolus PO x 1 slice?" I ask, as we pull into the fire station.

My fire preceptor grins at me, taking off his turnout pants. "Go back to bed," he says.